Vaughan Williams - James Gilchrist - International Record Review

Famounsly, A.E. Housman disliked music, and musical settings of his poetry. Yet, A Shropshire Lad is full of a most profound verbal music, a searing, plangent, very English melancholy that brings tears to the eyes of all but the most heart-hearted. (If you don't believe me, try an experiment: take down your copy, shut the door for half an hour, and read the 63 short poems straight through at a sitting. You'll be a different person at the end.)

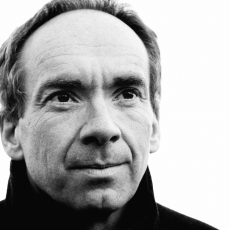

Many composers have quarried Housman in the past. I have a particular soft spot for the Arthur Somervell settings - but there is no denying pride of place to the great Vaughan Williams cycle (1909) with piano and string quartet. Over the years it has received some fine recordings at the hands of almost every English tenor to note, from Peter Pears to John Mark Ainsley: over those same years I have encountered many of them, and for my money the 1971 Ian Partridge version is unsurpassed for beauty of sound and interpretative insight. However, this newcomer is very fine: James Gilchrist's voice is perhaps not hugely individual, quite ‘white' in the timbre but utterly without any sense of strain at top or bottom, the diction crystal-clear and unaffected. There is a fine musical intelligence at work too: the climax of the heart-rending song ‘Is my team ploughing?' is unerringly identified and subtly underlined at the line ‘I cheer a dead man's sweetheart', and I liked, too, the hint of irritated rebelliousness at ‘O noisy bells, be dumb' in ‘Bredon Hill'. Is the final song, ‘Clun', a touch too fast? I am note sure.

Gilchrist also scores with his coupling, another lesser-known Housman sequence for the same combination. Gurney's Ludlow and Teme I have known since acquiring the Adrian Thompson version when it first came out in 1990: an interesting note by Philip Lancaster in the new Linn recording, however, claims that this is the first performance to incorporate Gurney's many post-publication annotations and corrections, all designed, in the composer's own phrase, towards the ‘taking away of squareness'. As far as I can tell, it is mostly a matter of myriad small details rather than of major surgery, though Gurney did remove occasional whole bars. Perhaps the finest of the seven settings - I have never really felt that they add up to a cycle in the way the Vaughan Williams seems to, and nor was Gurney possessed of his predecessor's melodic gifts - is ‘Far in a western brookland', realized here by all concerned in a fine, hushed reading. The sound on this recording, incidentally, is ideal for this repertoire: intimate and natural but still with sufficient resonance and space to let the music bloom.

Peter Warlock's setting of Yeats's Curlew poems is uncharacteristically austere, and he found the ideal combination for the sparse accompaniment by replacing the piano with the flute and (particularly) cor anglais, while keeping the string quartet. Once again Gilchrist gives a most sensitive rendition: I had moments of imagining it even bleaker still, but it has all the virtues listed above. As does the final short item, an expressive setting by Bliss of words specially written by Cecil Day Lewis for a commemorative concert for the pianist Noel Mewton-Wood, who had been the soloist in the composer's Piano Concerto some years earlier. This is a most imaginative and desirable combination of some of the finest English word-setting of the last century, and offers unfailing pleasure throughout.