Fitzwilliam String Quartet - Shostakovich: Last Three String Quartets - MusicWeb International

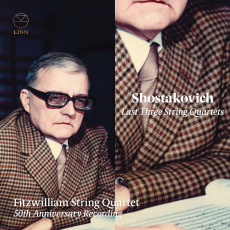

The Fitzwilliam String Quartet celebrates its fiftieth anniversary with a new recording of Shostakovich’s last three string quartets, looking back to the music through which they first became known. Shostakovich entrusted the Fitzwilliam with the western premieres of these last three quartets, and they were the first to perform and record all fifteen, that Decca set winning high praise. Thus the Fitzwilliam has an honoured place in the initial international reception of these works and their establishment in the canon. Benjamin Britten reported after Shostakovich’s death in 1975 that the composer had told him the Fitzwilliam were his preferred performers of his quartets.

There have been changes of personnel since then of course, and only violist Alan George still plays in the quartet. But what are the musical differences? As we have seen with the most recent of the three cycles by the Borodin Quartet, a change of personnel, and/or a deeper understanding, is reflected most obviously in a slowing down. This is quite consistent in the case of this new Fitzwilliam disc, compared to the 1970’s versions. This might in part be due to the absence of the composer, who had a dread of boring the first audiences and wanted players often to speed up (though not in the 15th quartet). But surely it is also to do with a greater sense of the music’s value, its established place in the chamber music repertoire, and affection for it. The more performances, the more nuances to uncover and convey to the hearers.

Quartet no.13 is the only single-movement form in the series and is dedicated to the former viola player of the Beethoven Quartet, the group who premiered all but one of Shostakovich’s quartets. The viola occupies the foreground from the outset, with a solo announcement of the twelve note row that provides much of the material. Founding member and sole survivor of the original line up, Alan George, plays this with what sound like heartache – helped of course by those falling semitones that recur throughout. In fact although this version is only 73 seconds longer than that of the 1970’s, one really feels the difference in the slow music. Thus the opening section up to fig. 10 (the switch to doppio movimento) took 4:30 in the 70’s, but 4:50 in 2019. The middle of the work has an even greater ‘dance of death’ feeling than before, and the final section, complete with those sinister knocks on the body of the instruments, has the same remarkable intensity as the opening.

No.14 is the most approachable of Shostakovich’s last three quartets, more melodious and less austere than the two flanking it. It is in three movements, with the second and third linked by an attacca marking. It is the last one to bear a dedication to a member of the Beethoven quartet, and this time it is the cellist that is honoured, including being given the opening dance tune and several duets with the leader. In one of these, in the adagio at fig.53, the cello soars into the tenor clef and plays above the violin, a very expressive effect. These duets enable us to hear the talent of those players, as good as any in this music, including even their predecessors in the Fitzwilliam Quartet. The finale is a delight, not least its shadowy waltz and a moving envoi from the cello.

The six movements of no.15 are slow and all marked adagio (adagio molto in the case of the funeral march), so it is not surprising that it is the longest of all fifteen quartets in duration. This must requires considerable concentration to pull off in performance, and it gets that here, helped by very slow tempi. In fact this is the slowest that I know, and like the Beethoven Quartet, and the Borodin Quartet’s third recording, one that manages to exceed the 37 minute mark. Shostakovich was aware of the challenge of sustaining such a pulse, and famously told the first performers "play it so that flies drop dead in mid-air, and the audience starts leaving from sheer boredom." The opening Elegy is a haunting fugue, immaculately played. The Fitzwilliam respect the markings pretty much all the time (and although a drop from p to pp at fig.7 does not really register, that is a rarity). The ppp to sffff crescendi that open the second movement Serenade are terrifying, as are some of the ff double stopped chords in all four instruments at the close – some serenade! The Intermezzo and Nocturne are not exactly light relief, but the intensity of the playing is modified a little to reflect the differing character of those movements, so that the implacability of the Funeral March, and the bleakness of the Epilogue, register their uncompromising finality. At the end - 37:48 from the start - the floor was surely covered in dead flies and the hall left empty.

This is a very fine set of the last quartets, unyielding in its commitment to this amazing music. The recording is close and realistic, with plenty of detail that captures the astonishing variety of texture. The informative booklet is very full indeed, with 27 pages (English only). I don’t know of a direct competitor to this issue, but the individual volumes 4 and 5 of the Mandelring quartet’s series will get you these works plus three others, and in a superior SACD recording. But if you want the full Soviet-era head-in-hands experience of these demanding pieces, this is the one.