Dunedin Consort - Handel: Samson - Gramophone

Amid Handel’s fluctuating fortunes in London’s cultural marketplace, Samson remained a reliable banker. Its popularity quickly spread beyond the capital, bolstered by two ‘hit’ numbers, Samson’s starkly simple ‘Total eclipse’ and the soprano’s ‘Let the bright seraphim’; and for two centuries and more after Handel’s death it probably received more performances than any of his oratorios bar Messiah and Israel in Egypt. Despite the static first act, Newburgh Hamilton’s adaptation of Milton’s Samson Agonistes is one of the best librettos Handel set, and the one most aligned to Greek tragedy. Its dramatic confrontations between the divinely chosen yet fatally flawed hero and his adversaries, including his former wife, inspired some of Handel’s most colourful, powerfully characterised music, culminating in an elegy (added by Hamilton) that rivals Saul’s in poignancy.

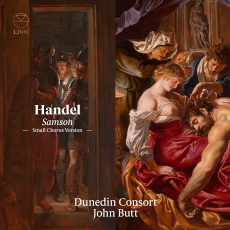

In the surprisingly sparse Samson discography, the clear winner has long been the direct, unfussy version from Harry Christophers and The Sixteen (Coro, 8/97), with typically polished, spirited choral work and a well-chosen cast. Recreating what was performed at the 1743 Covent Garden premiere – which means no funeral march after Samson’s death – John Butt’s superbly played and sung new recording, likewise made in the ideal, glowing acoustic of St Jude-on-theHill in Hampstead Garden Suburb, strikes me as even better. From the Philistine revels of ‘Awake the trumpet’s lofty sound!’ to the grave intensity of the requiem for Samson, the choruses, with the singers placed in front of the orchestra, have a thrilling immediacy. Following known Handelian precedent, the soprano line mixes women, including the soloists, with boy trebles (here from Tiffin School) to produce a flavoursome combination of richness and brightness. In his Handel’s Dramatic Oratorios and Masques (OUP: 1959), scholar Winton Dean provocatively invoked Verdi’s ‘Dies irae’ in the scene of the Philistines’ destruction (‘Hear us, O God!). The Dunedin forces, more operatically vivid than The Sixteen, make Dean’s point. At the other end of the spectrum, John Butt’s broader tempo enhances the nobility of the final chorus of Act 1, ‘Then round about the starry throne’.

One novelty here, explained in the booklet (which includes illuminating essays by Ruth Smith and Butt himself), is that the choruses have been recorded twice. The version you hear on the CD uses a full choir of around 40 singers, while the other, only available digitally, comprises the eight soloists plus a second alto. This slimmeddown approach again has Handelian precedent, though the resultant clarity never quite compensates for the loss of sonorous grandeur. With no weak link, Butt’s soloists are at least a match for Christophers’s. In the title-role, tenor Joshua Ellicott lacks the heroic weight of Christophers’s dark-toned Thomas Randle but drew me more deeply into Samson’s plight: in his spiritual anguish (‘Total eclipse’ is moving in its quiet inwardness and lack of rhetoric), in the graphic encounters with Dalila and the Philistine heavy Harapha, and in his serene, cathartic ‘Thus when the sun’, where Butt’s spacious tempo again pays dividends. Sophie and Mary Bevan, both natural Handelian stylists, are well-nigh ideal. Sophie, slightly richer and darker in tone than her sister, sings Dalila’s arias with seductive grace and gives every bit as good as she gets in the slanging match of ‘Traitor to love’. Mary’s ‘Let the bright seraphim’ is delightful in its mingled buoyancy and refinement of detail.

Jess Dandy, a true contralto, is the oratorio’s voice of balm, singing the sublime prayer ‘Return, O God of hosts’ with warm, even tone and broad phrasing. Her distinctive fast vibrato may initially disconcert some, though I quickly got used to it. As Samson’s father Manoah, Matthew Brook fields a ripe yet agile bass. His chastened tenderness in ‘How willing my paternal love’ is profoundly moving. Though not quite happy in the runs of ‘Honour and arms’, Vitali Rozynko makes a darkly formidable Harapha, relishing the Philistine’s sarcastic taunting of Samson. Soprano Fflur Wyn and tenor Hugo Hymas, singing with attractive youthful tone, do well in supporting roles. While those who already own the Christophers recording need not rush to replace it, this new Samson now becomes the top recommendation: for its uniformly excellent soloists, its excitingly ‘present’ choral singing and, above all, its more urgent sense of theatre. If you’re tempted, the muscular ‘Fix’d in his everlasting seat’, graphically pitting Dagon against Jehovah, or the Israelites’ imploring ‘With thunder armed’ should clinch it.