Chœur de Chambre de Namur - Arcadelt - MusicWeb International

As I write this we are at the period of commemorating the death on October 4th 1568 of ‘the divine’ Jacques Arcadelt, 450 years ago and this unique and superbly produced boxed set tells you all you need to know about this wonderful composer of some of the most beautiful madrigals in the repertoire. Astonishingly the recording was made just four months before the finished item, with its magnificent 142-page booklet, popped through my letterbox.

But its not just madrigals we have here as can be seen; chansons and sacred works feature equally. But, its worth pointing out that there are extant c.130 French chansons as well as over 200 madrigals.

These three discs which make up the box set have all been especially recorded by, various specialist groups of experienced ‘early’ musicians. They are each exquisitely and sensitively performed with just a few reservations.

I don’t know why I was again so surprised to find that Arcadelt had written and published quite a reasonable number of motets and masses especially as back in 2011 I reviewed a disc of his church music recorded by the Josquin Capella under Meinolf Bruser (CPO 777 763-2). I listened to some of it again whilst preparing this review and sfeel that my comment “a most pleasing disc offering a sound introduction to Arcadelt’s sacred works” still applies but I have come to realise that these perfromances sometimes miss much of the musical drama; this new recording is also beautifully performed; there is a clarity of texture in these works which the singers, due to a controlled and even tone quality and an ideal balance, bring out agreeably.

The motets enable the listener better to grasp Arcadelt’s stylistic background. The composers Josquin, (was Arcadelt really his pupil?) Gombert especially in the earlier motets with their continuous, imitative counterpoint (for example in ‘Momento salutis auctor’) and Willaert, although Arcadelt’s 8-part setting of the ‘Pater noster ‘does not, in fact, use the Venetian ‘cori spezzati’ technique. Particularly interesting is ‘Domine non secundum’ in which verse one is in three parts, verse two in four parts and the third verse in five parts but stylistically is the most complex and advanced. The performance however does not quite convince me, being rather unvaried in tone quality and dynamic.

Interest in Arcadelt started 150 years or so ago as reflected in the meditative organ piece by Liszt and the arrangement of the homophonic Ave Maria by the little known Dietsch.

It is the madrigals that are the area of Arcadelt’s output which is best known, many having been anthologised by Oxford, Penguin, Chester’s and many others and the most famous is ‘Il bianco I dolce cigno’. Its one of those pieces, so simple and yet so subtle which, no matter how often you hear it or sing it, as I have countless times, it never palls or loses its interest. This piece opens the set as it does indeed for another disc of Arcadelt’s secular works recorded by Anthony Rooley in 1991 (Deutsche Harmonia Mundi RD 77162) with Emma Kirkby.

Arcadelt emerges as one of the earliest of the Italian madrigal composers along with the slightly older but great Philip Verdelot (1480-1532) who was also very prolific. Both composer’s style and technique emphasised the melodic element as found in the popular Frottolas of Tromboncino (1470-1535) and Marcetto Cara (d.c.1525). Examples of this influence can be heard to a certain extent in, for example ‘Deh fuggite, o mortali’ but Arcadelt’s prime achievement consists of perfecting a clean four-part polyphonic texture. The five-part texture explored a little in some of the sacred works was still an intriguing new possibility in the madrigal. Interestingly however the CD ends with a six-part madrigal, ‘Amorosetto fiore’ that may, it’s said, be intended as homage to Josquin. But it was otherwise the 4-part format that burgeoned during the 1530’s and 40’s with a spate of publications. The performances reflect all of these considerations.

What I especially like is the variety of performing options employed and the use of instruments. These may double all four parts or accompanying a soloist (‘Occhi, miei lassi’) or indeed the voices may be a capella as in ‘Mentre gli ardenti rai’ or instruments be heard alone (‘Amour se pliant de ton forfeit’) or the same madrigal performed in two different ways (‘Non mai sempre fortuna’). There are a variety of sounds, which add to vary the palette and create further interest over the hour or so of vocal music. There is some proof, in the visual arts at least, that this is exactly how the music was performed. The instruments used are mostly lutes and a guitar with occasional use of harpsichord and even organ. Arcadelt’s works are characterised by an intensive expression, even a sentimentality, which the purity of the voices capture, and these lighter, chamber -type instruments enhance.

The approach here is to mix the various madrigal books so that if the ‘primo libro’ was indeed the most often reproduced we have sufficient opportunities to compare later publications side-by-side. Amazingly in 1539 it seems that no less than three books were brought out followed by more in the following two years. The first book on its reprint contained 60 madrigals but some have been attributed to lesser lights like Corteccia and Sebastian Festa likewise in volumes 3,4 and 5. There is also a so-called ‘Primo libre’ of Madrigals in 3-parts (‘Tante son le mie pene’)

The poets are rarely named in madrigal collections but with Arcadelt things are different. So we have two Petrarch settings here, including the quite dissonant ‘Crudel, acerba, inesorabil Morte’, even Arcadelt’s employer the ill-fated Lorenzo De Medici, who wrote ‘Vero inferno’ and Michelangelo, who was no mean poet. (‘Deh! dimni’ Amor se l’alma di costei’). It has been speculated, cogently I think, that Arcadelt would have known the artist, as they were both in Rome in the later 1530’s.

Anyway this is a perfect disc for this repertoire and I have much enjoyed it.

It came again as something of a surprise to me to discover that Arcadelt had not only published many French chansons but that some were even published within the Italian madrigal collections. But of course, French was Arcadelt’s mother tongue and although there is a great deal of stylistic similarity between the chansons and the madrigals I would also add that Arcadelt had, it seems to me, a deeper understanding of the inner meaning of the texts and the French style. Its interesting also that these pieces were published by men like Pierre Attaignant and Le Roy et Ballard from 1548 right up to reprints in 1572. Its also a testimony to the popularity of these pieces that composers like Trabaci were arranging the chansons for solo instruments half a century after Arcadelt’s death.

There is still however an occasional ‘frottola’-like piece such as ‘Celle que j’estime tant’, also a song with the close imitation typical of Josquin (‘Vous n’aurez plus mes yeux’) as well as one which seems to use a more traditional melody (‘Margot labourez’) and others which simply change the words of a madrigal from Italian to French (‘Quand je me trouve’). Characteristics largely found in sacred works can also be heard in the chansons. Canonic writing as in the complex ‘Tout au rebours’ and contrasting homophonic passages against more severe counterpoint appear in many pieces.

The methods of performances employed by Doulce Memoire, a group which consists of five singers and six instrumentalists, are similar to those discussed above and this again gives distinction and diversity, which is a joy and a pleasure, and, I feel, there is an even greater variety of approach, texture and colour. The music can certainly be serous and thoughtful, especially where lost love is portrayed, but there are also many fun moments and amusing texts, which are strongly characterised by the singers.

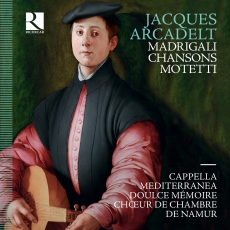

I’ve already touched on the booklet, which is very impressive, thorough and fascinating. We have an essay on ‘Arcadelt – a man from Namur’, ‘Arcadelt the Visionary’, ‘Arcadelt and the Chanson’, a six-page essay on Arcadelt’s career and influence, with separate essays on his madrigalian style, his chanson style and the style of his sacred music. There is also an essay entitled ‘Is this truly Jacques Arcadelt’ with a a reproduction of a painting on the CD box by Pontormo who knew Arcadelt (it is speculated) and may well have wanted to fashion his portrait. The individual cardboard CD holders are also adorned with a detail from a Renaissance painting. All texts are given in the original, English and French and there are photographs of the performers.